The Mutationism Myth (2): Revolution

Our journey began with The Mutationism Myth, part 1. Then, in Theory vs Theory, we took a brief detour to distinguish theoryC (concrete, conjectural) from theoryA (abstract, analytical). Today we are back to the Mutationism Myth and our goal is to probe its claim that the scientific community rejected Darwin’s ideas on erroneous grounds.1

The Mutationism Myth, 2. Revolution

The Mutationism Myth is a story told in the literature of neo-Darwinism, regarding the impact of the (re)discovery of Mendelian genetics a century ago. In this story, the discoverers of genetics (characterized as laboratory-bound geeks) misinterpret their discovery, thinking it incompatible with natural selection; the false gospel of these “mutationists” brings on a dark period that lasts until the 1930s, when theoretical population geneticists prove that genetics is the missing key to Darwinism; Darwinism is restored, and there is peace and unity in the land.

In typical versions of the mutationism story that we reviewed in part 1, the Mendelians cast a spell on the scientific community, convincing it of a false belief that either

- Mendelian genetics is inconsistent with the concept of natural selection or

- selection is irrelevant because mutational jumps alone explain evolution

For instance, Eldredge (2001) writes:

Many early geneticists at the dawn of the 20th century, thought their discoveries of the fundamental principles of genetics somehow cast doubt [on], or rendered obsolete, the concept of natural selection

As noted earlier, a myth is not necessarily false. Some parts of the Mutationism Myth reflect history accurately, and others do not. An underlying truth in the Mutationism Myth is that, as a direct result of the re-discovery of Mendelian genetics, leading geneticists— Bateson, Johannsen, de Vries, Morgan, Punnett, and others— rejected Darwin’s theory for how evolution works.

Our goal is to understand why. We must begin with heredity, the heart of the issue.

Re-discovering a lost theory

The re-discovery of Mendel’s theory of heredity was nothing short of a revolution, and if you were trained in 19th-century views of heredity, this would be obvious, and there would be no need for me to explain it.

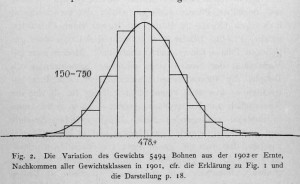

Unfortunately, the chances are good that you, dear reader, have been trained in the principles of Mendelism, and that puts us at a disadvantage. Once we learn of the genotype-phenotype distinction and the purity of hereditary factors, these principles seem to change our view of the world irreversibly, and its hard to understand what came before. Johannsen’s quantitative-genetics experiments on seed weights of the Princess bean, conducted in the first decade of the 20th century, appear to have had more impact on evolutionary thinking than any single study conducted before or since. In the figure below, Johanssen (1903) shows the distribution of weights of beans from a plot planted with a mixture of seeds from pure self-fertilizing lines (the legend says “The variation of the weight of 5494 beans from the 1902 harvest, descendants of all weight classes in 1901”) (online source)

The beans from the mixed plot show a nice bell-shaped distribution. Similarly, the beans harvested from pure lines grown in separate garden plots also show nice bell-shaped distributions, though the means differ for each pure line. The key difference is in the results of selective breeding for heavier (or lighter) beans, i.e., planting a new crop using only the heaviest (or lightest) beans: selection shifts the distribution of seed weights in the mixed plot, but has no significant effect on the distribution of seed weights produced by a pure line.

Within just a few decades, neo-Darwinians such as Ford (1938) dismissed Johannsen’s results as a logical necessity, as though the experiments proved nothing. Johannsen’s studies had changed our understanding so profoundly that Ford was unable to imagine how scientists (mis)understood the world before.

I won’t ask you to do what Ford could not, which is to forget genetics. What we might be able to do, instead, and what I will ask you to do, is to imagine a different world— one in which particulate inheritance of pure hereditary factors does not apply.

We have been sent to this alien world as evolutionary experts, to consult with its scientists about how evolution might work on their planet. The alien scientists explain that, in their world, the bodies of organisms have differentiated organs composed of diverse cell-like subunits (CLSs), which swell, fuse, split and exchange material. The CLSs don’t seem to have nuclei or central control centers. Instead, they are composed of substances that interact productively and grow, crystal-like (possibly some kind of prion-like protein, we think to ourselves). Different CLSs have different compositions, and thus have different developmental tendencies, e.g., some CLSs have a tendency to aggregate and interact to form a differentiated organ.

We are skeptical of the alleged lack of nuclei, so we explain the “nucleus” concept to the aliens and propose that CLSs actually have a spatially localized store of information that controls growth and development. The aliens listen carefully and ask clarifying questions in order to understand our hypothesis. Then they tell us that they know we are wrong. Alien scientists long ago developed a method of splitting CLSs which showed that the separated parts of CLSs largely retain their potential for growth and development, even if the CLSs are cut in multiple pieces. Thus, the alien scientists had demonstrated that CLSs and their substances have a hereditary aspect, but the potential for heredity seems to be dispersed in the substances, not centralized in a nucleus.

During the life of an organ, CLSs may come and go. CLSs circulating in the body are harvested continually in the reproductive organs, where substances are extracted to form minute reproductive corpuscles, RCs, whose role in reproduction is similar to gametes. However, the RCs or reproductive corpuscles don’t have the 1-copy-of-each-factor neatness of earthly Mendelian gametes. The growable substances in the RCs are variable in amount, thus RCs vary in potency. Furthermore, the composition of CLSs circulating in the body reflects the totality of what is happening in the body: because the body is continually growing and reacting and changing, the RCs are changing, too. In particular, the composition of the RCs tends to deviate more strongly when the organisms are stressed or face unusual conditions.

While some of the alien organisms are asexual, others have tri-parental reproduction that involves mixing of RCs from different parents. Each of the 3 parents makes a contribution of RCs, typically equal in size— though in some species, one type of parent contributes much more than the other two. When the parental RCs come together, the substances in them seem to mix or blend.

A different kind of evolution

The alien scientists have outlined the basic ideas of heredity on their planet, and they are looking to us expectantly for answers about how evolution is going to work. We were hoping to gather more facts, and particularly to hear from other experts about the diversity of life, and so on, but the aliens are eager for our ideas right away. What can we infer about evolution in a bottom-up manner, from an understanding of heredity?

We see immediately that it will be possible to apply some concept of “selection” in this world, but its going to be awfully slippery. We reach into our conceptual toolbox, and the first thing we find is the concept of “selection coefficient”. But thats not useful on the alien planet, because there is no stable genetic entity to which one may apply the selection coefficient— everything in the alien world with a bearing on heredity seems to be variable in potency and to be subject to blending. Heredity depends on the differential growth of continuous substances, modulated by their differential incorporation into RCs due to conditions of life, and so on. The alien world lacks the algebraic neatness of pairwise combinations and pure factors.

In fact, our hearts sink as we realize that, because of this blending-together, it might be impossible for evolution to start from a single hereditary variant, as would be possible on earth starting with a single Mendelian mutant. The distinctive features of the individual variant would simply diffuse and blend.

But our discouragement is only temporarily. Yes, it would have been simple and easy if hereditary factors emerged discretely, combined in simple ratios, and maintained their purity during reproduction— but who said science was supposed to be simple and easy?

We are undaunted. We are determined to discover some way to apply the principle of selection. In fact, given that the RCs deviate more strongly under unusual conditions, we note with enthusiasm that extra hereditary variation will emerge just when it would be helpful to provide fuel for adaptation to new conditions! Due to hereditary blending, one variant individual, with a variation in a favorable direction, would not be enough. But thats not a problem. In fact, to treat it as a “problem” is wrong-headed, because this alien world is not a world of discrete heredity anyway! Instead, on the alien planet, heredity is a bulk process, like the flow and mixing of liquids! The hereditary substances flow (metaphorically) in new directions every generation, and selection can get some leverage from these fluctuations of hereditary potency, even if there is not any single discrete particle to grasp. Selection would guide these fluctuations, building them smoothly from generation to generation. Possibly we could develop a mathematical formalism for this process by adapting Price’s equation, or the breeder’s equation of quantitative genetics, although the shifting of hereditary potencies from one generation to the next would be problematic. An even more radical thought occurs to us: Lamarckian evolution can’t happen in our world, but in the alien world, it just might be possible due to the way the RCs reflect what is going on in the body as it experiences its environment.

If you have followed me thus far, congratulations! You are one of the re-discoverers of Darwin’s lost theory of evolution!

Evolution without mutation

Sadly, when I refer to a “lost theory”, its not a joke, because Darwin’s “Natural Selection Theory” (not to be confused with the principle of natural selection2) is largely unknown to contemporary scientists. During the Darwin bicentennial last year, I lost track of how many times “Darwin’s theory” was explained by reference to “selection and random mutation” or some such anachronism.

Darwin had no such theory. Given Darwin’s assumptions that inheritance is blending (not particulate), that the germ-line is responsive to external conditions (not isolated), and that hereditary potencies shift gradually every generation (not rarely and abruptly, from one pure, stable state to another), it is physically impossible for a rare trait, having arisen by some process, and conferring a fitness advantage of (for example) 2 %, to be passed on to offspring by a stable non-blended hereditary factor, thus conferring on the offspring a 2 % advantage, and for such a process to continue for thousands of generations until the previously rare trait prevails. We may think of evolution in this way: Darwin did not.

Instead, Darwinism 1.0 (Darwin’s conception of evolution) is an automatic process of adjustment to altered conditions, dependent on a rampant process of “fluctuation” yielding abundant “infinitesimally small inherited modifications” in response to the effect of altered “conditions of life” on the “sexual organs” (Chs. 1, 2, 4 and 5 of Darwin 1859). Fluctuation was not rare and discrete, but shifted hereditary factors continuously and cumulatively each generation, producing visible effects in “several generations” (Ch. 1 of Darwin 1859). Muller (1956) referred to Darwinian fluctuation as “creeping variation”. I have called it “variation on demand”, and I also think that, to understand Darwin’s view, its helpful to think of heredity and variation as processes mediated by fluids (liquids or gases). Darwin’s critics, and many of his supporters such as Huxley and Galton, believed that individual “sports” (mutants) could be the start of something new in evolution, but this was not part of Darwin’s theory, which invoked blending inheritance and held fast to natura non facit salta.

For those who would like to get more of a flavor of Darwin’s view from his own writings, I have included a few passages below in small print below; readers may wish to go further by browsing online sources via the links provided. Others may wish to take a colorful look at Darwin’s laws of variation from the Virtual Museum of the Origin of Species.

Two passages below illustrate Darwin’s view of the emergence of hereditary variation. In the second passage he is describing a breeder’s experiment in domestication from wild duck eggs— Darwin learned about heredity by exchanging hand-written letters with men such as Mr. Hewitt.

“It seems clear that organic beings must be exposed during several generations to new conditions to cause any great amount of variation; and that, when the organisation has once begun to vary, it generally continues varying for many generations.” (Origin of Species, Ch. 1; online source)

“If strange and rare deviations of structure are really inherited, less strange and commoner deviations may be freely admitted to be heritable. Perhaps the correct way of viewing the whole subject would be, to look at the inheritance of every character whatever as the rule, and non-inheritance as the anomaly” (Darwin, 1859, Ch. 1; online source).

“Mr. Hewitt found that his young birds always changed and deteriorated in character in the course of two or three generations; notwithstanding that great care was taken to prevent their crossing with tame ducks. After the third generation his birds lost the elegant carriage of the wild species, and began to acquire the gait of the common duck. They increased in size in each generation, and their legs became less fine. The white collar round the neck of the mallard became broader and less regular, and some of the longer primary wing-feathers became more or less white. When this occurred, Mr. Hewitt destroyed nearly the whole of his stock and procured fresh eggs from wild nests; so that he never bred the same family for more than five or six generations. His birds continued to pair together, and never became polygamous like the common domestic duck. I have given these details, because no other case, as far as I know, has been so carefully recorded by a competent observer of the progress of change in wild birds reared for several generations in a domestic condition. “(Darwin, 1883, p. 293; online source)

Thus, Darwin is describing subtle variations that emerge in response to new conditions, and that emerge immediately or, at least, within a few generations. He saw hereditary fluctuation as an effectively continuous process, i.e., a process that can be subdivided arbitrarily in time and in outcome because it is the summation of infinitesimal increments. Adaptation can happen rapidly and reliably because organisms start to vary immediately upon encountering new conditions. Similar variations will be manifested in many individuals (as in the case of the ducks above), so that multiple members of a “race” may emerge and interbreed simultaneously with, or prior to, selection. This avoids the problems posed by the swamping effect of blending inheritance (Darwin did not believe that a solitary variant could begin an evolutionary change). Darwin’s principles of variation are roughly that

- hereditary variation emerges in response to “altered conditions of life” (e.g., domestication);

- the process is so rapid and productive that visible effects appear in one or a few generations;

- continuous (“infinitesimal”, “insensible”) fluctuations occur in virtually all characters;

- some effects are definite or reliable (“all or nearly all the offspring of individuals exposed to certain conditions during several generations are modified in the same manner”), while others are “indefinite” (isotropic);

- definite effects reflect mainly internal (developmental) causes, but also external (environmental) and Lamarckian causes (“effects of use and disuse”).

To account for his principles or “laws”3 of variation, Darwin proposed a “gemmule” theory for the mechanism of heredity, where “gemmules” are somewhat like the RCs or “reproductive corpuscles” in the fictional alien world described above.

Although Darwin’s “Natural Selection” theory invoked Lamarckian effects, the fluctuation-selection process that Darwin called “Natural Selection” was recognized immediately as its mechanistic core. Only this core mechanism remains in the reformed view of Weismann and Wallace— “Darwinism 1.2” for our purposes—, which expunged Lamarckism and relied on selection of ever-present fluctuations, a process understood (in Darwinism 1.2) as the exclusive and all-powerful driving force of evolution.

“Natural Selection” and heredity

<!–

One issue that we will not address today, but will address in a future post, is the ambiguity surrounding the phrase “natural selection”, which is a major contributor to murkiness in evolutionary discourse. The mutationists rejected “Natural Selection”, the theoryC of Darwin, but not natural selection, the generic principle of reproductive sorting. In a later post, we will explore how the ambiguity in “natural selection” covers up a multitude of sins [challenge to the reader: spot the fallacy in charlesworth comment on kirschner & gerhardt] . And we’ll consider ways to speak (and think) more clearly and rigorously.

A second issue that we will not address is the distorting influence of the cult of personality that has developed around Darwin, which instills in so many scientists the irrational desire to label themselves “Darwinists” while ignoring Darwin’s actual views, and when challenged, to make excuses for what Darwin got wrong (“he couldn’t have known!”), as though science were about aligning ourselves with people based on judgements of their scientific virtue, and not about dispassionately evaluating the truth or falsity of theories. In a future post, I will address the distorting influence of the Darwin Fetish, as well as the Fisher Fetish, and how to End the Reign of the DiNOs (Darwinians in Name Only).

A third murky issue warrants a few words. –> While Darwin’s “gemmule” theory for the mechanism of heredity is wrong, thats not whats wrong with the “Natural Selection Theory”— indeed, the “gemmule” mechanism was proposed after Darwin’s theory of evolution was proposed in The Origin of Species.

To understand why Darwin’s errant understanding of the mechanism of heredity is not relevant, lets compare Darwin to Newton for a moment. Newton provided a causal theory for planetary orbits (accounting for Kepler’s model of elliptical orbits) based on his laws of gravity and of motion applied to the planets as massive inertial bodies, but he did not propose a cause of gravity itself. He was a bit embarrassed about this, because the law of gravity seemed to invoke instantaneous action-at-a-distance. Nevertheless, the lack of a mechanism of gravity doesn’t matter to Newton’s theory of planetary orbits, so long as the law of gravity is correct.

Likewise, Darwin’s proposed a theory of evolution based on his laws of variation. Later he proposed a “gemmules” mechanism to account for the laws of variation. Thus, the “Natural Selection” theory can be separated from the “gemmules” idea, and in principle, we could maintain the broader theory and discard the “gemmules” explanation.

The reason that this is not sufficient to rescue Darwin’s theory is that it does not just get the underlying mechanism of heredity wrong: it gets the principles (“laws”) of heredity wrong. The “Natural Selection Theory” is based on the heritability of fluctuations. Whatever the mechanistic cause of fluctuations, they are defined as the “endless slight peculiarities which distinguish the individuals of the same species and which cannot be accounted for by inheritance from either parent or from some more remote ancestor” (Darwin, 1859, Ch. 1; online source). We now know the fluctuations that arise anew every generation in response to conditions, and that are not due to inheritance from the parents, are environmental variation, i.e., they reflect phenotypic plasticity in response to varying external conditions.

Developing a new view of evolution

In fact, the “Mendelians” did not reject the principle of selection. Instead, they rejected “fluctuation” as the basis of evolutionary change for exactly the reason we would expect, namely that these fluctuations are not heritable. This is what Johannsen’s experiments suggest: fluctuations that emerge reliably every generation, i.e., Darwin’s “endless slight peculiarities which distinguish the individuals of the same species and which cannot be accounted for by inheritance from either parent or from some more remote ancestor”, are non-heritable and cannot be the basis for evolution by natural selection.

This is precisely the reason that geneticists gave, explicitly, for rejecting Darwin’s view. For instance, in his 1911 book Mendelism, Punnett (of the “Punnett square” one studies in Genetics 101) explains the new view of the mechanistic “basis of evolution”:

“The distinction between these two kinds of variation, so entirely different in their causation, renders it possible to obtain a clearer view of the process of evolution than that recently prevalent. . . Evolution only comes about throught the survival of certain variations and the elimination of others. But to be of any moment in evolutionary change a variation must be inherited. And to be inherited it must be represented in the gametes. This, as we have seen, is the case for those variations which we have termed mutations. For the inheritance of fluctuations, on the other hand, of the variations which result from the direct action of the environment upon the individual, there is no indisputable evidence. Consequently we have no reason for regarding them as playing any part in the production of that succession of temporarily stable forms which we term evolution. In the light of our present knowledge we must regard the mutation as the basis of evolution– as the material upon which natural selection works. For it is the only form of variation of whose heredity we have any certain knowledge.

It is evident that this view of the process of evolution is in some respects at variance with that generally held during the past half century.” (Punnett, 1911, p. 139-140; online source)

Punnett rejects “fluctuations”, defined as “the variations which result from the direct action of the environment upon the individual”.

It wasn’t about rejecting natural selection. Punnett identifies mutation as the “basis” of evolution precisely on the grounds that it provides “the material on which selection works”. Likewise, while TH Morgan was suspicious of the phrase “natural selection”, he was not rejecting a role for differential effects of fitness when he wrote in 1916 that

“evolution has taken place by the incorporation into the race of those mutations that are beneficial to the life and reproduction of the organism” (p. 194) (online source)

That is how genetics eliminated Darwin’s original theory of evolution. If we want to understand the “basis” of evolution, the Mendelians argued, we must look to mutation, not look to Darwin’s “fluctuations”.

That was merely the start of a new way of looking at evolution. In the next installment, we’ll find out what sort of understanding of evolution emerged among this new generation of evolutionists inspired by Mendelian principles. We’ll see that, contrary to the Mutationism Myth, the period between the discovery of genetics and the origin of the Modern Synthesis in the 1930s was not a dark period of confusion at all, but a period of innovation that gave rise to key elements of the genetics-based understanding of evolution that persists today, including new ways of understanding selection.

Loose ends

A major goal of The Curious Disconnect is to clarify issues that are murky, and I can’t leave this issue without pointing out some of the muck. For instance, the ambiguity surrounding the phrase “natural selection”, which is a major contributor to murkiness in evolutionary discourse. The mutationists rejected “Natural Selection”, the theoryC of Darwin, but not natural selection, the generic principle of reproductive sorting. In a later post, we will explore how the ambiguity in “natural selection” covers up a multitude of sins [challenge to the reader: spot the fallacy in charlesworth comment on kirschner & gerhardt] . And we’ll consider ways to speak (and think) more clearly and rigorously.

A second issue that we will not address today is the distorting influence of the cult of personality that has developed around Darwin, which instills in so many scientists the irrational desire to label themselves “Darwinists” while ignoring Darwin’s actual views. When challenged, the cultists make personal excuses (“he couldn’t have known!”) for aspects of Darwin’s theory that were proved wrong, as though science were about judging persons rather than evaluating theories. In a future post, we’ll explore the distorting influence of the Darwin Fetish (hopefully we will have time to discuss the Fisher Fetish, too).

A third issue has to do with the relation of “laws” and “mechanisms” to falsification, in this particular case. While Darwin’s “gemmule” theory for the mechanism of heredity is wrong, thats not the real issue. To understand why, lets compare Darwin to Newton for a moment. Newton provided a causal theory for planetary orbits (accounting for Kepler’s model of elliptical orbits) based on his laws of gravity and of motion applied to the planets, but he did not propose a cause of gravity itself. He was a bit embarrassed about this, because the law of gravity seemed to invoke instantaneous action-at-a-distance. Nevertheless, the lack of a mechanism of gravity doesn’t matter to Newton’s theory of planetary orbits, so long as the law of gravity is correct. If the law were abandoned later, this would remove the foundation of Newton’s theory of the planets.

Darwin proposed a theory of evolution based on his laws of variation. It hardly matters that he proposed a “gemmules” mechanism to account for the laws of variation, because the laws themselves were wrong. That is, Darwin’s theory does not just get the underlying mechanism of heredity wrong, it gets the principles (“laws”) of heredity wrong: the “Natural Selection Theory” is based on the heritability of fluctuations. Whatever the mechanistic cause of fluctuations, they are defined as the “endless slight peculiarities which distinguish the individuals of the same species and which cannot be accounted for by inheritance from either parent or from some more remote ancestor” (Darwin, 1859, Ch. 1; online source). We now know that the kind of fluctuations that arise anew every generation in response to conditions, and that are not due to inheritance from the parents, are environmental variations, i.e., they reflect phenotypic plasticity in response to varying external conditions. That is, the fluctuation law of hereditary variation was wrong.

Note that, initially, Mendelism corrected only the “laws” (principles) of heredity and did not offer a mechanism for them. An understanding of the underlying physiology of heredity heredity emerged later, as Morgan and colleagues developed a chromosome theory, and the behavior of Mendelian factors was related to the microscopically observable assortment of chromosomes in dividing cells.

Darwin espoused a theory of evolution, not merely a principle of selection. If Darwin’s “Natural Selection” theory merely asserted the principle of selection, then no possible finding in genetics could contradict his theory. In fact, Darwin’s theory invoked the principle of selection, in the context of a mechanism he called “fluctuation”, to account for most of the actual facts of evolution, leaving a residue to be explained by other means (Lamarckian and Buffonian effects)— other means that Darwin’s followers soon rejected as untenable, leaving only the fluctuation-selection process.

Thus, prior to the discovery of genetics, Darwin’s theory was understood correctly to rely on the kind of instantaneous and continuous variation that Darwin called “fluctuation”, and which was induced by environmental conditions. Geneticists rejected this incorrect view of hereditary variation, and thus they rejected the theory that relied on it.

Little of this is understood today, because “Darwinism” or “Darwin’s theory” has been redefined, and the original meaning of “Darwin’s theory” has gone done the proverbial memory hole.

References

Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species. John Murray, London.

Darwin, C. 1883. Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. D. Appleton & Co., New York.

Eldredge, N. 2001. The Triumph of Evolution and the Failure of Creationism. W H Freeman & Co.

Ford, E. B. 1938. The Genetic Basis of Adaptation. Pp. 43-56 in G. R. de Beer, ed. Evolution. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Morgan, T. H. 1916. A Critique of the Theory of Evolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Punnett, R. C. 1911. Mendelism. MacMillan.

Ridley, M. 2002. Natural Selection: An Overview. Pp. 797-804 in M. Pagel, ed. Encyclopedia of Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York.

Notes

1 An updated version of this post will be available at <a href=”https://www.molevol.org/cdblog/mutationism_myth2″>https://www.molevol.org/cdblog/mutationism_myth2</a>

2 Blame Darwin and his followers, not me, for this egregious ambiguity.

3 Today we would call these laws “principles” or “generalizations”. “Laws” in 19th century science are empirical generalizations, reached by the method of Baconian induction: collect lots of facts and distill them into generalizations.

Credits: The Curious Disconnect is the blog of evolutionary biologist Arlin Stoltzfus, available at www.molevol.org/cdblog. An updated version of the post below will be maintained at www.molevol.org/cdblog/mutationism_myth2 (Arlin Stoltzfus, ©2010)